Contents: Introduction * Anglo-Saxon * Arabic * Armenian * Coptic: Sahidic, Bohairic, Other Coptic versions * Ethiopic * Georgian * Gothic * Latin: Old Latin, Vulgate * Old Church Slavonic * Syriac: Diatessaron, Old Syriac, Peshitta, Philoxenian, Harklean, Palestinian, "Karkaphensian" * Udi (Alban, Alvan)

The New Testament was written in Greek. This was certainly the best language for it to be written in; it was flexible and widely understood.

But not universally understood. In the west, there were many who spoke only Latin. In the east, some spoke only the Syriac/Aramaic dialects. In Egypt the native language was Coptic. And beyond the borders of the Roman Empire there were peoples who spoke even stranger languages -- Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic, Gothic, Slavonic.

In some areas it was the habit to read the scriptures in Greek whether people understood it or not. But eventually someone had the idea of translating the scriptures into local dialects (we now call these translations "versions"). This was more of an innovation than we realize today; translations of ancient literature were rare. The Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible was one of the very first. Despite the lack of translations in antiquity, it is effectively certain that Latin versions were in existence by the late second century, and that by the fourth there were also versions in Syriac and several of the Coptic dialects. Versions in Armenian and Georgian followed, and eventually many other languages.

The role of the versions in textual criticism has been much debated. Since they are not in the original language, some people discount them because there are variants they simply cannot convey. But others note, correctly, that these versions convey texts from a very early date. In many instances the text-types they represent survive very poorly or not at all in Greek.

It is true that the versions often have suffered corruption of their own in the centuries since their translation. But such variants usually are of a nature peculiar to the version, and so can be gotten around. When properly used, the versions are one of the best and leading tools of textual criticism.

This essay does not attempt to fully spell out the history and limitations of the versions. These points will briefly be touched on, but the emphasis is on the textual nature of the versions. Those who wish to learn more about the history of the versions are advised to consult a reference such as Bruce M. Metzger's The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission, and Limitations (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1977).

In the list which follows, the versions are listed in alphabetical order.

An additional note: Of all the articles in this Encyclopedia, apart from those which touch on science and theology. this has been among the most controversial. I don't mean that people disagree with the results particularly; that happens everywhere. But this one seems to make people most upset. Please note that I am not setting out to belittle any particular version, and except in textual matters, I am not expert on these versions. I will stand by the statements on the textual affinities of the more important versions (Latin, Syriac, Coptic; to a lesser extent, the Armenian, Georgian, and Gothic) insofar as they are correctly incorporated into the critical apparatus. For the history and such, I am dependent upon others. If you disagree with the information here, I will try to incorporate suggestions, but there is only so much I can do to make completely contradictory claims fit together....

Although Roman Britain was Christian, the Anglo-Saxon invasions of the late fifth century effectively wiped out Roman Christianity. And it would be centuries before Christianity completely took control of the island, because the German invaders immediately split the island into dozens of small states, of which seven survived to become the "Seven Kingdoms of Britain": Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex, Essex, Sussex, Kent, and East Anglia. To make matters worse, all these kingdoms had slightly different dialects.

It was in 563 that Saint Columba founded the religious center on Iona, bringing Celtic Christianity back to northern Britain. In 596 Pope Gregory the Great sent Augustine to Canterbury to return southern Britain to Christ. The two Christian sects were formally reconciled at the Synod of Whitby in 664. This did not make Britain Christian (and, ironically, it did not bring Ireland into line with Catholic Christianity; that island, now known for its Catholicism, was brought back into line with the Catholic church by the Anglo-Norman invaders), but the way was at last clear.

The earliest attempts at Anglo-Saxon versions probably date from this time, but they have not survived. Nor has the translation of John made by the Venerable Bede. Alfred the Great worked at a translation, but it seems never to have been completed. All that is known to have existed is a portion of the psalms, including a detailed (though often fanciful) commentary said to have been by Alfred himself. (In this connection it may be worth noting that Asser, Alfred's biographer, at several points quotes the Bible in Old Latin rather than Vulgate forms.)

Our earliest surviving Anglo-Saxon versions date from probably the tenth century. Several of these are continuous text versions; the most famous of these is probably the Hatton Gospels, now in the Bodleian; this beautifully-written manuscript is thought to be from the eleventh century. Other Old English renderings are interlinear glosses to Latin manuscripts. The interlinears are in several dialects.

In many ways the Anglo-Saxon was better suited to literal Bible translation than is modern English, since Anglo-Saxon is an inflected language with greater freedom of word order than modern English. Since, however, all Anglo-Saxon translations are taken from the Latin (unless Bede made some reference to the Greek), they are not generally cited for New Testament textual criticism. This is proper -- though they perhaps deserve more attention for Vulgate criticism; it should be recalled that the early English copies of the Vulgate were of very high value, so the translations could well derive from valuable originals.

We should note that the term "Anglo-Saxon" is now frowned upon by linguists, who much prefer the term "Old English." I have yet to see this term applied to the early English translations. The name "Anglo-Saxon" seems to be used in the same sense that "Ethiopic" is used for a version that is in a language not properly called "Ethiopic": It's a geographic/historical description.

|

Arabic translations of the New Testament are numerous. They are also very diverse. They are believed to have been made from, among others, Greek, Syriac, and Coptic exemplars. Other sources may be possible. |

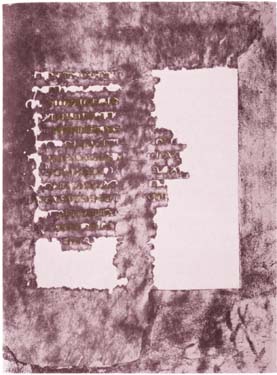

Folio 1 recto of Sinai Arabic 71 (Xth century), Matthew 23:3-15. |

Although there are hints in the records of Arabic versions made before the Islamic conquests, the earliest manuscripts seem to date from the ninth century. The oldest dated manuscript of the version (Sinai arab. 151) comes from 867 C.E. The translations probably are not more than a century or two older.

Several of the translations are reported to be very free. In any case, Arabic is a Semitic language (which, like Hebrew, has a consonantal alphabet, leaving room for interpretation of vowels) and frequently cannot transmit the more subtle nuances of Greek grammar. In addition, written Arabic was largely frozen by the Quran, while the spoken language continued to evolve and develop regional differences. This makes the Arabic versions somewhat less vernacular than other translations. This would probably tend to preserve the original readings, but may result in some rather peculiar variants.

The texts of the Arabic versions have not, to this point, been adequately studied. Some seem to be purely or primarily Byzantine, but at least some are reported to contain "Cæsarean" readings. Others are said to be Alexandrian. Still others, with something of an "Old Syriac" cast, may be "Western."

Several late manuscripts preserve an Arabic Diatessaron. The text exists in two forms, but both seem to have been influenced by the Peshitta. They are generally regarded as having little value for Diatessaric studies.

It will be obvious that the Arabic versions are overdue for a careful study and classification.

The Armenian translation of the Bible has been called "The Queen of the Versions."

The title is deserved. The Armenian is unique in that its rendering of the New Testament is clear, accurate, and literal -- and at the same time stylisticly excellent. It also has an interesting underlying text.

The origin of the Armenian version is mysterious. We have some historical documents, but these may raise more questions than they solve.

The most recent summary on the subject, that of Joseph M. Alexanian, states that the initial Armenian translation (Arm 1) was made from the Old Syriac in 406-414 C.E. This was followed by a revised translation (Arm 2) made from the Greek after the Council of Ephesus in 431. He suggests that further revisions followed.

In assessing Alexanian's claims, one should keep in mind that there are no Armenian manuscripts of this era, and the patristic citations, while abundant, have not been properly studied or catalogued.

Armenia is strongly linked with Syrian Christianity. The country turned officially Christian before Constantine, in an era when the only Christian states were a few Syriac principalities such as Edessa. One would therefore expect the earliest Armenian versions to show strong signs of Syriac influence.

The signs of Syriac influence exist (among them, manuscripts with 3 Corinthians and without Philemon) -- but so do signs of Greek influence. In addition, the text of the Armenian matches neither the extant Old Syriac nor the Peshitta. It appears to be much more closely linked with the "Cæsarean" text. In fact, the Armenian is arguably the best witness to that text.

The history of the Armenian version is closely tied in with the history of the written Armenian language. After perhaps an unsuccessful attempt by a cleric named Daniel, the Armenian alphabet is reported to have been created by Mesrop, the friend and co-worker of the Armenian church leader Sahak. The year is reported to have been 406, and the impetus for the invention is said to have been the need for a way to record the Armenian Bible. Said translation was finished in the dozen or so years after Mesrop began his work.

Despite Alexanian, the basis of the version remains in dispute. Good scholars have argued both for Syriac and for Greek. There are passages where the wording seems to argue for a Syriac original -- but others that argue equally forceably for a Greek base.

|

A portion of one column of the famous Armenian MS. Matenadaran 2374 (formerly Etchmiadzin 229), dated 989 C.E. Mark 16:8-9 are shown. The famous reference to the presbyter Arist(i)on is highlighted in red. | At least three explanations are possible for this. One is that the Armenian was translated from the Greek, but that the translator was intimately familiar with a Syriac rendering. An alternate proposal is that the Armenian was translated in several stages. The earliest stage was probably a translation from one or another Old Syriac versions, or perhaps from the Syriac Diatessaron. This was then revised toward the Greek, perhaps from a "Cæsarean" witness. Further revisions may have increased the number of Byzantine readings. Finally, there may have been two separate translations (Conybeare suggests that Mesrop translated from the Greek and Sahak from the Syriac) which were eventually combined. |

The Armenian "Majority Text" has been credited to Nerses of Lambron, who revised the Apocalypse, and perhaps the entire version, on the basis of the Greek in the twelfth century. This late text, however, has little value; it is noticeably more Byzantine than the early text. Fortunately, the earliest Armenian manuscripts are much older than this; a number date from the ninth century. The oldest dated manuscript comes from 887 C.E. (One manuscript claims a date of 602 C.E., but this is believed to be a forgery.)

There are a few places where the Armenian renders the Greek rather freely (usually to bring out the sense more clearly); these have been compared to the Targums, and might possibly be evidence of Syriac influence.

The link between the Armenian and the "Cæsarean" text was noticed early in the history of that type; Streeter commented on it, and even Blake (who thought the Armenian to be predominantly Byzantine) believed that it derived from a "Cæsarean" form. The existence of the "Cæsarean" text is now considered questionable, but there is no doubt that the Armenian testifies to a text which is far removed from the Byzantine, and that it contains large numbers of Alexandrian readings as well as quite a number associated with the "Western" witnesses. The earliest witnesses generally either omit "Mark 16:9-20" or have some sort of indication that it is doubtful (the manuscript shown above may credit it to the presbyter Arist(i)on, though this remark is possibly from a later hand). "John 7:53-8:11" is also absent from most early copies.

In the Acts and Epistles, the Armenian continues to display a text which is not Byzantine but not purely Alexandrian either. Yet -- in Paul at least -- it is not "Western." Nor does it agree with family 1739, nor with H, both of which have been labelled (probably falsely) "Cæsarean." If the Armenian has any affinity in Paul at all, it is with family 2127 -- a late Alexandrian group with some degree of mixture. This is not really surprising, since one of the leading witnesses to the family is 256, a Greek/Armenian diglot (in fact, the Armenian text of 256 is one of the earliest witnesses to the Armenian Epistles).

Lyonnet felt that the Armenian text of the Catholic Epistles fell close to Vaticanus. In the Apocalypse, Conybeare saw an affinity to the Latin (in fact, he argued that it had been translated from the Latin and then revised -- as many as five times! -- from the Greek. This is probably needlessly complex, but the Latin ties are interesting. Jean Valentin offers the speculation that the Latin influence comes from the Crusades, when the Armenians and the Franks were in frequent contact and alliance.)

The primary edition of the Armenian, that of Zohrab, is based mostly on relatively recent manuscripts and is not really a critical edition (although some variant readings are found in the margin, their support is not listed). Until a better edition of the version becomes available -- an urgent need, given the quality of the translation -- the text of the version must be used with caution.

The language of Egypt endured for at least 3500 years before the Islamic conquest swept it aside in favour of Arabic. During that time it naturally underwent significant evolution.

There was at one time much debate over the origin of the Egyptian language; was it Semitic or not? It seemed to have Semitic influence, but not enough to really be part of the family. This seems now to have been solved; Joseph H. Greenburg in the 1960s proposed to group most of the languages of northern Africa and the Middle East in one great "Afroasiatic" superfamily. Egyptian and the Semitiic languages were two of the families within this greater group. Thus Egyptian is related to the Semitic languages, but at a rather large distance.

Coptic is the final stage of the evolution of Egyptian (the words "Copt"

and "Coptic" are much-distorted versions of the name "Aigypt[os]").

Although there is no clear linguistic divide between Late Egyptian and

Coptic, there is something of a literary one: Coptic is Egyptian written

in an alphabet based on the Greek. It is widely stated that the Coptic alphabet

(consisting of the twenty-four Greek letters plus seven letters -- give

or take a few -- adopted from the Demotic) was developed because the old

Egyptian Demotic alphabet was too strongly associated with paganism.

This seems not to be true, however; the earliest surviving documents in the

Coptic alphabet seem to have been magical texts.

It is at least reasonable to suppose that the Coptic alphabet was adopted because it was an alphabet -- the hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic styles of Egyptian are all syllabic systems with ideographic elements. And both hieratic and demotic have other problems: Hieratic is difficult to write, and demotic, while much easier to copy, is difficult to read. And neither represents vowels accurately. Some scribe, wanting a true alphabetic script, took over the Greek alphabet, adding a few demotic symbols to supply additional sounds.

Coptic finally settled down to use the 24 Greek letters plus six or seven demotic symbols. It was some time before this standard was achieved, however; early texts often use more than these few extra signs. This clearly reveals a period of experimentation.

Coptic is not a unified language; many dialects (Akhmimic, Bohairic, Fayyumic, Middle Egyptian, Sahidic) are known. The fragmentation of Coptic is probably the result of the policies of Egypt's rulers: The Romans imposed harsh controls on travel in and out of, and presumably within, Egypt; before them, the Ptolemies has rigidly regimented their subjects' lives and travels. After a few hundred years of that, it is hardly surprising that the Egyptian language ceased to be unified.

New Testament translations have been found in all five of the dialects listed; in several instances there seem to have been multiple translations. The two most important, however, are clearly Sahidic (the language of Upper Egypt) and Bohairic (used in the Lower Egyptian Delta). Where the other versions exist only in a handful of manuscripts, the Sahidic endures in dozens and the Bohairic in hundreds. The Bohairic remains the official version of the Coptic church to this day, although the language is essentially extinct in ordinary life.

The history of the Coptic versions has been separated into four stages by Wisse (modifying Kasser). For convenience, these stages are listed below, although I am not sure of their validity.

A more detailed study of the various versions follows.

The Sahidic is probably the earliest of the translations, and also has the greatest textual value. It came into existence no later than the third century, since a copy of 1 Peter exists in a manuscript from about the end of that century. Unlike the Bohairic version, there is little evidence of progressive revision. The manuscripts do not always agree, but they do not show the sort of process seen in the Bohairic Version.

Like all the Coptic versions, the Sahidic has an Egyptian sort of text.

In the Gospels it is clearly Alexandrian, although it is sometimes considered to

have "Western" variants, especially in John. (There are, in fact,

occasional "Western" readings in the manuscripts, but no pattern

of Western influence. Most of the so-called "Western" variants

also have Alexandrian support.) As between B and , the Sahidic is

clearly closer to the former -- and if anything even closer to P75. It is

also close to T (a close ally of P75/B) -- as indeed one would expect,

since T is a Greek/Sahidic diglot.

In Acts, the Sahidic is again regarded as basically Alexandrian, though with some minor readings associated with the "Western" text. In the "Apostolic Decree" (Acts 15:19f., etc.) it conflates the Alexandrian and "Western" forms. (One should note, however, the existence of the codex known as Berlin P. 15926. Although its language is to be Sahidic, its text differs very strongly from the common Sahidic version, and preserves a number of striking "Western" variants found also in the Middle Egyptian text G67.)

In Paul the situation is slightly different. Here again at first glance the Sahidic might seem Alexandrian with a "Western" tinge. On examination, however, it proves to be very strongly associated with B, and also somewhat associated with B's ally P46. I have argued elsewhere that P46/B form their own text-type in Paul. The Sahidic clearly goes with this type, although perhaps with some influence from the "mainstream" Alexandrian text.

In the Catholics, the Sahidic seems to have a rather generic Alexandrian text, being about equidistant from all the other witnesses. It is noteworthy that its more unusual readings are often shared with B.

The Bohairic has perhaps the most complicated textual history of any of the Coptic versions. The oldest known manuscript, Papyrus Bodmer III, contains a text of the Gospel of John copied in the fourth (or perhaps fifth) century. This version is distinctly different from the later Coptic versions, however; the underlying text is distinct, the translation is different -- and even the form of the language is not quite the same as in the later Bohairic version. For this reason it has become common to refer to this early Bohairic version as the "proto-Bohairic" (pbo).From the same era comes a fragment of Philippians which may be a Sahidic text partly conformed to the idiom of Bohairic.

Other than these two minor manuscripts, our Bohairic texts all date from the ninth century or later. It is suspected that the common Bohairic translation was made in the seventh or eighth century.

It is quite possible that this version was revised, however; there are a number of places where the Bohairic manuscripts split into two groups. Where this happens, it is fairly common to find the older texts having a reading typical of the earlier Alexandrian witnesses while the more recent manuscripts often display a reading characteristic of more recent Alexandrian documents or of the Byzantine text. One can only suspect that these late readings were introduced by a systematic revision.

As already hinted, the text of the Bohairic Coptic is Alexandrian. Within

its text-type, however, it tends to go with rather than B. This is

most notable in Paul (where, of course,

and B are most distinct).

Zuntz thought that the Bohairic was a "proto-Alexandrian" witness

(i.e. that it belonged with P46 B sa), but in fact it is one of

's

closest allies here -- despite hints of Sahidic influence, which are found

in the other sections of the New Testament as well. One might theorize that

the Bohairic was translated from the Greek (a manuscript with a late Alexandrian

text), but with at least some Sahidic fragments used as cribs.

The Akhmimic (Achmimic). Possibly the most fragmentary of all the versions. Fragments preserve portions of Matthew 9, Luke 12-13, 17-18, Gal. 5-6, James 5. All of these seem to be from the fourth or perhaps fifth centuries. Given their small size, very little is known of the text of the Akhmimic. Aland cites it under the symbol ac.

Related to the Akhmimic, and regarded as falling between it and the Middle Egyptian, is the Sub-Akhmimic. This exists primarily in a manuscript of John, containing portions of John 2:12-20:20 and believed to date from the fourth century. It seems to be Alexandrian, and is cited under the symbol ac2 or ach2.

The Fayyumic. Spelled Fayumic by some. Many manuscripts exist for the Gospels, and over a dozen for Paul, but almost all are fragmentary. Manuscripts of Acts and the Catholic Epistles are rare; the Apocalypse seems to be entirely lost (if, indeed, it was ever translated). Manuscripts date from about the fifth to the ninth centuries. There is also a fragment of John, from perhaps the early fourth century, which Kahle called Middle Egyptian but Husselman called Fayyumic. This mixed text is now designated the "Middle Egyptian Fayyumic (mf)" by Aland. (The Fayyumic is not cited in NA27; the abbreviation fay is used in UBS4.)

Given the fragmentary state of the Fayyumic, its text has not been given much attention. In Acts it is reported to be dependent on the Bohairic, and hence to be Alexandrian. Kahle found that an early manuscript which contained both the long and short endings of Mark.

The Middle Egyptian. The Middle Egyptian Coptic is represented primarily by three manuscripts -- one of Matthew (complete; fourth/fifth century), one of Acts (1:1-15:3; fourth century), and one of Paul (54 leaves of about 150 in the original; fifth century). The Acts manuscript, commonly cited as copG67, is perhaps the most notable, as it agrees frequently with the "Western" witnesses, including some of the more extravagant variants of the type. The Middle Egyptian is cited by Aland under the symbol mae; UBS4 uses meg.

Although the origins of many of the versions are obscure, few are as obscure as those of the Ethiopic. The legend that Christianity was carried to the land south of Egypt by the eunuch of Acts 8:26f. can be easily dismissed. So can accounts that one of the apostles worked there. Even if one or more of these stories were true, they would not explain the existence of the Ethiopic version. (The New Testament hadn't even been written at the time of the Ethiopian's conversion in Acts.)

Even the name of the version is questionable; the correct name for the official language of Ethiopia is Amharic, and the manuscripts of the "Ethiopic" version are in an old form of this language.

A legend told by Rufinus has it that Christianity reached Ethipia to stay in the fourth century. Although this is beyond verification, there are indications that Christianity did indeed reach the country at that time.

Unlike many of the languages into which the Bible was translated, Ethiopia already had developed writing at the time Christianity reached the country (the alphabet resembles the Semitic in that it uses letters for consonants and lesser symbols for vowels; however, the letter forms diverge widely from the Phoenician, and the language reads from left to right. It has been theorized that the Ethiopic alphabet is actually derived from the Old Hebrew alphabet, abandoned by the Jews themselves in the post-Exilic period. The modern "Hebrew" alphabet is actually Aramaic. Ethiopic, however, added vowel symbols at a very early date -- not as extra letters but as tags attached to letters -- in effect, a syllabary. This is further evidence of Semitic origin -- and, probably, of the absence of Greek influence).

Because written Ethiopic predates the New Testament, we cannot date the version based on the dates of the earliest written documents. Nor are the dates of the earliest manuscripts much help, since all Ethiopic manuscripts are of the eleventh century or later and the vast majority are of the fourteenth century or later. Nor did printing immediately affect the version; manuscripts continued to be copied into the seventeenth century and even beyond. Perhaps the most common theory is that the version dates from about the fifth century, when Christianity probably became widespread in Ethiopia.

It is not clear what language formed the translation base for the Ethiopic version, although Greek and Coptic are the leading candidates (the Apocalypse, in particular, contains a number of transliterations from Greek) It is possible that both were used in different books. Syriac and Arabic have also been mentioned (the version bears significant orthographic similarities to those languages), and revisions based on the latter cannot be ruled out. On the other hand, Ethiopic is not Indo-European, so many of the noteworthy features of Greek (e.g. noun declensions, word order, and many verb forms) cannot be rendered. Hints of Syriac or Arabic influence on the version may simply be because Ethiopic is closer to those languages. The problem is not simplified by the fact that the language is not well-known to scholars and the version has not been properly edited. In addition, it appears likely that different translators worked on different books (since the style ranges from the free to the stiltedly literal); it is possible that different base texts were used. It is worth noting that the Ethiopic Bible includes several works not normally considered canonical.

Based on the available information, it would appear that the Ethiopic has an Alexandrian text -- but an uncontrolled, with very primitive Alexandrian readings alternating with primarily Byzantine readings and some variants that are simply wild. Zuurmond calls it "Early Byzantine" in the Gospels, and also notes an "extreme tendency toward harmonizations." Hoskier noted that Eth had a number of unusual agreements with P46 in Paul, but undertook no detailed study. It may be that the Ethiopic is based on the sort of free text that seems to have prevailed in Egypt in the early years of Christianity: Basically similar to the Alexandrian text, with a number of very primitive readings (the latter often rather rough), but with some wild readings, others characteristic of the later text, and a number of readings that resulted simply from scribal inattentiveness. The lack of a detailed study prevents us from saying more.

If any version is most notable for our ignorance about its origin, it is the Georgian. The language is difficult and not widely know (it is neither Indo-European nor Semitic; the alphabet, known as Mkhedruli, is used only for this language. Georgian is the only language of the Kartvelian group to have a written form), the country small, and the history of the translation is obscure. Whatever its origins, however, the version is of great textual significance.

Please note that plain HTML and pure ASCII, in which this document is written, has no facilities even for transliterated Georgian; I've done my best with the technical terms, but you really need to visit a specialized site to see the correct forms of the letters.

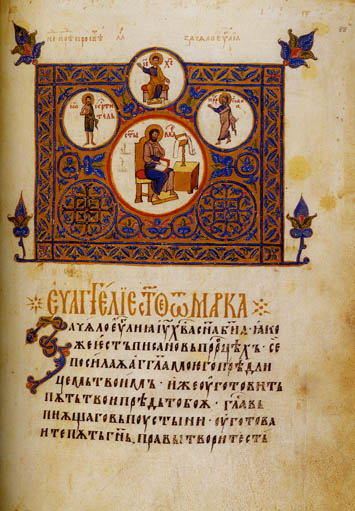

|

Legend has it that the evangelist of the Georgians, a woman named Nino, came to Georgia as a slave during the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine. Another legend has it that the Georgian alphabet was invented by Saint Mesrop some time after he had created the written form of Armenian. | Sinai Georgian 31, dated 877, folio 54 verso,

Acts 8:24-29.

|

Both of these legends may be questioned -- the former on historical grounds, the latter on the basis of its simple improbability. It is by no means certain that the Georgian alphabet was invented to receive a Biblical translation (if it had been, why is it so different from other alphabets?); the Georgian alphabet may well be older than the fifth century.

Given our ignorance of the history of Christianity in Georgia, we can only speculate about the history of the version. The latest possible date would appear to be the sixth century, since our earliest manuscripts (the "han-met'i fragments") are dated linguistically to that era, or perhaps even to the fifth century. The most likely date for the version is therefore the fifth century. This is supported by an account of the life of St. Shushanik, dated to the fifth century and containing many allusions to the Biblical text.

By its nature it is difficult for Georgian to express many features of Greek syntax. This makes it difficult to determine the linguistic source of the version. (Nor does it help that the language itself has evolved; the translation started in Old Georgian, but New Georgian came into existence from the twelfth century, and later manuscripts will have been influenced by the new dialect.) Greek, Armenian, and Syriac have all been proposed -- in some instances even by the same scholar! It seems clear that the version was at some time in its history revised toward the Greek -- but since manuscripts of the unrevised text are at once rather few and divergent, we probably cannot reach a certain conclusion regarding the source at this time. The current opinion seems to be that, except in the Apocalypse (clearly taken from the Greek), the base text -- what we might call the "Old Georgian," and now found primarily in geo1 and some of the fragments -- was Armenian, and that it was progressively modified by comparison with the Greek text.

The earliest Georgian manuscripts are the already alluded to han-met'i fragments of the sixth and seventh centuries, followed by the hae-met'i fragments of the next century. (The names derive from linguistic features of the Georgian which were falling into disuetitude.) These fragments are, unfortunately, so slight that (with the exception listed below) they are of little use in reconstructing the text (some 45 manuscripts contain, between them, fragments of the Gospels, Romans, and Galatians only). Recently a new han-met'i palimpsest was discovered and published, containing large portions of the Gospels, but the details of its text are not yet known; it appears broadly to go with the Adysh manuscript (geo1).

With the ninth century, fortunately, we begin to possess fuller manuscripts, of good textual quality, from which we may attempt to reconstruct the "Old Georgian" text. Many of these manuscripts, happily, are dated.

The earliest substantially complete Georgian text is the Adysh manuscript, a copy of the Gospels dating from 897 C.E. It appears to have the most primitive of all Georgian translations, and is commonly designated geo1.

From the next century come

the Opiza Gospels (913), the Dzruc Gospels

(936), the Parhal Gospels (973), the Tbet' Gospels (995),

the Athos Praxapostols (between 959 and 969), and the Kranim Apocalypse (978),

as well as assorted not-so-well-known texts. Several of these manuscripts

combine to represent a second stage of the Georgian version, designated

geo2. When cited separately, the Opiza gospels are

geoA, the Tbet' gospels are geoB.

(The Parhal Gospels are sometimes cited as geoC, but

this is not as common.)

Starting in the tenth century, the Georgian version was revised, most notably by Saint Euthymius of Athos (died 1028). Unfortunately, the resulting version, while perhaps improved in form and literary merit, is less interesting textually; the changes are generally in conformity with the Byzantine text.

The text of the Georgian version, in the Gospels, is clearly "Cæsarean" (assuming, of course, that text-type exists). Indeed, the Georgian appears to be, along with the Armenian, the purest surviving monument of that text-type. Both geo1 and geo2 preserve many readings of the type, though not always the same readings. Blake thought that geo1 affiliated with Q 565 700 and geo2 with families 1 and 13.

In Acts, Birdsall links the Old Georgian to the later forms of the Alexandrian text found in minuscules such as 81 and 1175. In Paul, he notes a connection with P46, although this exists in scattered readings rather than as an overall affinity. In the Apocalypse, the text is that of the Andreas commentary.

Of all the versions regularly cited in critical apparati, the Gothic is probably the least known. This is not because it is ignored. It is because it has almost ceased to exist.

The Gothic version was apparently entirely the work of Ulfilas (Wulfilas), the Apostle to the Goths. Appointed Bishop to the Goths around 341, he spent the next forty years evangelizing and making the gospel available to his people. In the process he created the Gothic alphabet. The picture shows that it was based on Greek and Latin models, but also included some symbols from the Gothic runic alphabets.

Ulfilas translated both Old and New Testaments, from the Greek (reportedly

excepting the book of Kings, because it was too militant for his flock), but

only fragments of the New Testament survive. (At that, they are the almost only

literary remains of Gothic, a language which is long since dead.)

The gospels are preserved primarily in the Codex Argenteus of the sixth century. Even this manuscript has lost nearly half its pages, but enough have survived to tell us that the books are in the "Western" order (Matthew, John, Luke, Mark), and that the manuscript included Mark 16:9-20 but omitted John 7:53-8:11. The image of the manuscript at right demonstrates this; the page contains John 7:52, 8:12-17.

Other than the Argenteus, all that has come to light of the gospels are a small portion of Matthew from a palimpsest and a few fragmentary verses of the Luke on a Gothic/Latin leaf destroyed during the Second World War.

According to Metzger, nothing has survived of the Acts, Catholic Epistles, and Apocalypse. Vincent Broman tells me that the Old Testament is almost all lost, though there is a fragment of Nehemiah large enough to indicate a Lucianic ancestor. Of Paul there are several manuscripts, all fragmentary and all palimpsest. Only 2 Corinthians is complete, and Hebrews is entirely lacking. (It has been speculated that Ulfilas, for theological or other reasons, did not translate Hebrews, but Broman informs me that it has been quoted in a commentary.)

Ulfilas's version is considered literal (critics have called it "severely" literal, preserving Greek word order whether it fits Gothic or not). It is very careful in translation, striving to always use the same Gothic word for each Greek word. Even so, Gothic is a Germanic language, and so cannot distinguish many variations in the Greek (e.g. of verb tense; some word order variations are also impermissible). It is also possible, though by no means certain, that Ulfilas (who was an Arian preaching to Arians) allowed some slight theological bias to creep into his translation.

In the Gospels, the basic run of the text is very strongly Byzantine, although von Soden was not able to determine what subgroup it belongs with. Burkitt found a number of readings which the Gothic shared with the Old Latin f (10), though scholars are not agreed on the significance of this. Some believe that the Old Latin influenced the Gothic; others believe the influence went the other way. Our best hint may come from Paul. Here the Gothic is again Byzantine, but less so, and it has a number of striking agreements with the "Western" witnesses. It has been theorized that Ulfilas worked with a Byzantine Greek text, but also made reference to an Old Latin version. Presumably this version was either more "Western" in the Epistles, or (perhaps more likely) Ulfilas made more reference to it there.

It is much to be regretted that the Gothic has not been better preserved. While the Gospels text is not particularly useful, a complete copy of the Epistles might prove most informative. And it is, along with the Peshitta, one of the earliest Byzantine witnesses; it might provide interesting insights into the Byzantine text.

The handful of survivals are also of keen interest to linguists, as the Gothic is the earliest known member of the Germanic family of languages, predating the earliest Old English texts by a couple of centuries; it is also of significance as the only attested East Germanic language (the Germanic group is thought to have three families: The West Germanic, which includes all languages now called "German," plus English, Dutch, Frisian, and Yiddish; the North Germanic, which gave rise to Icelandig, Faroese, Swedish, Danish, and Norwegian, which are still mostly mutually intelligible and amount to hardly more than a single source; and the East Germanic, which consists solely of Gothic). Thus the Gothic is very important in reconstructing proto-Germanic -- and, indeed, Indo-European.

Of all the versions, none has as complicated a history as the Latin. There are many reasons for this, the foremost being its widespread use. The Latin Vulgate was, for millennia, the Bible of the western church, and after the fall of Constantinople it was the preeminent Bible of Christendom. There are at least eight thousand Latin Bible manuscripts known -- or at least two thousand more Latin than Greek manuscripts.

The first reference to what appears to be a Latin version dates from 180 C.E. In the Acts of the Scillitan Martyrs, one of the men on trial admits to having writings of Paul in his possession. Given the background, it is presumed that these were in a Latin version.

But which Latin version? That is indeed the problem -- for, in the period before the Vulgate, there were dozens, perhaps hundreds. Jerome, in his preface to the Vulgate gospels, commented that there were "as many [translations] as there are manuscripts." Augustine complained that anyone who had the slightest hint of Greek and Latin might undertake a translation. They seem to have been right; of our dozens of non-Vulgate Latin manuscripts, no two seem to represent exactly the same translation.

| Below: An Old Latin manuscript, Codex Sarzensis (j), on purple parchment, much damaged by the gold ink used to write it. Shown in exaggerated color | Modern scholars have christened these pre-Vulgate translations, which generally originated in the second through fourth centuries, the "Old Latin." (These versions are sometimes called the "Itala," but this term is quite properly going out of use. It arose from a statement of Augustine's that the Itala was the best of the Latin versions -- but we no longer know what this statement means or which version(s) it refers to.) |

The Old Latins are traditionally broken up into three classes, the African, the European, and the Italian. Even these terms can be misleading, however, as there is no clear dividing line between the European and the Italian; the Italian generally refers to European texts of a more polished type -- and in any case these are groups of translations, not individual translations.

The Old Latin gospels generally, although by no means universally, have the books in the "Western" order (Matthew, John, Luke, Mark) -- an order found also in D and W but otherwise very rare among Greek manuscripts.

The oldest of the types is probably the African; at least, its renderings are the crudest, and Africa was the part of the Roman Empire which had the smallest Greek population and so had the greatest difficulty with a Greek Bible. In the first century, Greek was as common in Rome as was Latin; it was not until several centuries later (as the Empire became more and more divided and Greek-speaking slaves became rarer) that Italy and the west felt the need for a Latin version. Eventually the demand became so great that Pope Damasus authorized the Vulgate.

Traditionally the Old Latin witnesses were designated by a single Roman letter (e.g. a, b, e, k). As Roman letters ran out, longer names (aur) or superscripts (g1) came into use. The Beuron Latin Institute has now officially numbered the Old Latin witnesses (of which about ninety are now known), but the old letter designations are still generally used to prevent confusion with the minuscules.

The tables below show, section by section, the Old Latin witnesses available to the modern scholar. In general only those witnesses found in the NA27 or UBS4 editions are listed, although a handful of others (often Old Latin/Vulgate mixes) have been cataloged. Observant users will observe that this list omits some "Old Latin" witnesses cited in UBS4. Examples include ar c dem in Acts. The reason is that these are actually Vulgate witnesses with occasional Old Latin readings; they will be discussed under the Vulgate.

| Symbol | Beuron Number | Date | Name | Contents | Comments |

| a | 3 | IV | Vercellensis | e# | Seems to be an early form of the European Latin. Closest to b ff2, but perhaps with some slightly older readings. Deluxe manuscript (silver and gold ink on purple parchment), reputed to have been written by Saint Eusebius, Bishop pf Vercelli (martyred 370/1). It has been so venerated as a relic that certain passages have been rendered unreadable by worshippers' kisses. Contains Mark 16:9-20, but on interpolated leaves; C.H. Turner believes the original did not contain these verses. Text is regarded as similar to n in the Synoptic Gospels. |

| a2 | 16 | V | Curiensis | Lk 11#, 13# | cf. n, o (both also #16) |

| aur | 15 | VII | Aureus | e# | Primarily Vulgate but with many Old Latin readings.

Incidentally, combining references from several sources, it appears that this is the oldest surviving parchment manuscript with a separate title page (there seem to have been no others until shortly before the invention of printing). |

| b | 4 | V | Veronensis | e# | Purple codex with silver and some gold ink. Originally contained 418 leaves; 393 remain, some of which have decayed to the point of illegibility. Widely regarded as one of the very best European witnesses; almost all other witnesses of the type agree with b more than with each other. A few passages have been conformed to the Vulgate, in writing so like the original that the alterations were not noticed for many centuries. |

| b | 26 | VII | Carinthianus | Lk 1-2# | |

| c | 6 | XII/ XIII | Colbertinus | e(apcr) | Late and vulgate influenced, but apparently with some African readings (although European readings dominate; it is much closer to b ff2 than to k). The pre-vulgate readings are most common in Mark and Luke. The rest of the NT, which comes from another source, is Vulgate with scattered Old Latin readings. |

| d | 5 | V/ VI | Bezae | e#a#c# | Latin side of Codex Bezae, and almost as controversial as the Greek. It is probably based on an independent Latin version, since D and d disagree at some few points. However, they agree the vast majority of the time, even in places where they have no other Latin support. It is effectively certain that the two texts have been modified to agree more closely. The great question is, which has been modified, and to what extent? |

| d | 27 | IX | Sangallensis | e# | Latin interlinear of D, with no real value of its own. |

| e | 2 | V | Palatinus | e# | After k, the most important witness to the African Latin. (Unfortunately, the two overlap only very slightly, so it is hard to compare their texts.) Purple codex. |

| f | 10 | VI | Brixianus | e# | Purple codex. The text seems to fall somewhere between the (European) Old Latin and the vulgate, and it has been conjectured that it was the sort of manuscript Jerome made his revision from. However, it has links to the Gothic (it has been conjectured that it was taken from the Latin side of a Gothic-Latin diglot), which make this less likely. It is distinctly more Byzantine and less "Western" than the average Old Latin. It is considered to be an Italian text. |

| ff1 | 9 | VIII | Corbiensis | Mt | Vulgate with some Old Latin readings. |

| ff2 | 8 | V | Corbiensis | e# | European Latin, probably the best text of the type after b. |

| g1 | 7 | VIII/ IX | Sangermanensis | Mt(NT) | Old Latin in Matthew; rest is Vulgate (see Vulgate G) |

| h | 12 | V | Claromontanus | Mt#(e) | Old Latin in Matthew; rest is Vulgate. |

| i | 17 | V/VI | Vindobonensis | Mk#Lk# | Purple codex. |

| j | 22 | VI | Sarzanensis | (Lk#)Jo# | Purple codex. Text is described as "peculiar and valuable." |

| k | 1 | IV/ V | Bobiensis | Mt#Mk# | Best codex of the African Latin, unfortunately only about half complete even for the books it contains (it now consist of portions of Matt. 1:1-15:36 plus Mark 8:8-end). Noteworthy for containing only the short ending of Mark (without the long ending); it is the only known manuscript to have this form. Written in a good hand by a careless scribe -- quite possibly a non-Christian. The text seems to resemble Cyprian. |

| l | 11 | VIII | Rehdigeranus | e# | "Mixed text." |

| l | - | VIII/ IX | Lk 16-17# | ||

| m | - | V | Monacensis | Mt 9-10# | The symbol m is sometimes used for the Codex Mull (35 -- e/vii), which is probably an Old Latin heavily corrected toward the Vulgate. |

| n | 16 | V | Sangallensis | Mt#Mk#Jo# | Cf. a2, o (both also #16) |

| o | 16 | VII | Sangallensis | Mk# | Mark 16:14-20. Cf. a2, n (both also #16). |

| p | 20 | VIII | Sangallensis | Jo 11# | |

| p | 18 | VII | Stuttgartensis | Mt#Lk#Jo# | |

| f | - | V | |||

| q | 13 | VI/ VII | Monacensis | e# | Considered to have an Italian text, though perhaps with a slightly different textual base. Written in a clumsy hand by a scribe named Valerianus. |

| r1 | 14 | VII | Usserianus | e# | |

| r | 24 | VII/ VIII | Ambrosianus | Jo 13# | |

| s | 21 | VI/ VII | Ambrosianus | Lk 17-21# | |

| t | 19 | V/ VI | Bernensia | Mk 1-3# | |

| v | 25 | VII | Vindobonensis | Jo 19-20# |

| Symbol | Beuron Number | Date | Name | Contents | Comments |

| d | 5 | V/ VI | Bezae | e#a#c# | Latin side of Bezae (D). See comments in the section on the Gospels. |

| e | 50 | VI | Laudianus | a# | Latin side of Laudianus (E). The base text is considered to be European, but there is also assimilation to the parallel Greek. |

| g | Symbol used in some editions for gig. | ||||

| gig | 51 | XIII | Gigas | (e)a(pc)r | An immense codex containing the Bible and a number of other works. Its text in Acts is reminiscent of that of Lucifer of Cagliari, but experts cannot agree whether it belongs with the African or European Latin. |

| h | 55 | V | Floriacensis | a#c#r# | Fleury palimpsest. The translation is loose and the copy careless, but the text is very close to that used by Cyprian (African). |

| l | 67 | VII | Legionensis | a#c# | Palimpsest; text is vulgate with some sections of Old Latin readings (Acts 8:27-11:13, 15:6-12, 26-38). Said to be close to the Liber Comicus (t) |

| (m) | - | IV? | (Speculum) | eapcr | See Speculum under Fathers |

| p | 54 | XII | Perpinianus | a | Old Latin in 1:1-13:6, 28:16-end. The text is said to be similar to the fourth century writer Gregory of Elvira, and is thought to have been written in northern Spain or southern France. |

| ph | 63 | XII | a | Acts with "other material." | |

| r | 57 | VII/ VIII | Schlettstadtensis | a# | Lectionary |

| ro | 62 | X | Rodensis | (e)a(pcr) | Vulgate text with Old Latin readings in both text and margin in Acts. |

| s | 53 | VI | Bobiensis | a# | Palimpsest |

| sa | 60 | XIII | Boverianus | a# | Contains Acts 1:15-26. |

| sin | 74 | X | a#r# | ||

| t | VII+ | Liber Comicus | a#p#c#r# | Lectionary | |

| w | 58 | XIV/ XV | Wernigerodensis | (e)a(p)c(r) | Vulgate with Old Latin readings in Acts & Catholics. |

Note: Scholars generally do not distinguish between African, European, and Italian texts in Paul (although I have seen r called both African and Italian). The reason seems to be that we have no unequivocally African texts.

| Symbol | Beuron Number | Date | Name | Contents | Comments | |

| a | 61 | IX | Dublinensis (Book of Armagh) | (ea)p#(c)r | General run of the text is vulgate text with many Old Latin readings, but Paul (vac. 1 Cor. 14:36-39) and the Apocalypse are Old Latin with some Vulgate influence. See D of the Vulgate for full information on the history and style of this noteworthy manuscript. | |

| b | 89 | VIII/ IX | p | Close to d, and possibly the best Latin witness available in Paul. Most other "Western" witnesses are closer to b d than to each other. | ||

| comp | 109 | p | ||||

| d | 75 | VI | Claromontanus | p# | Latin side of D. Unlike most bilinguals, the Latin and the Greek do not appear to have been conformed to each other; d seems to fall closest to b. | |

| f | 78 | IX | Augiensis | p# | Latin side of F. Mixed Vulgate and Old Latin (Hebrews is purely Vulgate), possibly with some assimilation to the Greek text. | |

| g | 77 | IX | Boernianus | p# | Latin interlinear of G. Rarely departs from the Greek text except where it offers alternate renderings. | |

| gue | 79 | VI | Guelferbytanus | Rom# | Palimpsest, from the same manuscript as Pe Q. Contains Rom. 11:33-12:5, 12:17-13:1, 14:9-20. Merk's w. | |

| (m) | - | IV? | (Speculum) | eapcr | See Speculum under Fathers. Not to be confused with m/mon (below) | |

| m | 86 | X | p# | The appendix of NA27 lists this as mon (the latter symbol is used in UBS), but cites it in the text as m. Not to be confused with the Codex Speculum, often cited as m. The text is said to be similar to that of Ambrose; it is noteworthy for placing the doxology of Romans after chapter 14 (so also gue; neither ms. exists for Romans 16). | ||

| mon | Symbol used for m in UBS4. | |||||

| m | 82 | IX | Monacensis | Heb 7, 10# | Contains Heb. 7:8-26, 10:23-39 | |

| p | 80 | VII | Heidelbergensia | Rom 5-6# | ||

| r | 64 | VI, VII | Frisingensia | p# | Assorted small fragments, sometimes denoted r1, r2, r3. They do not come from the same manuscript, but seem to have similar texts. They have a much more Alexandrian cast than the other Old Latins, and are said to agree with Augustine. Same as q/r of the Catholics. | |

| r | 88 | X | 2Co# | |||

| s | 87 | VIII | p# | Lectionary fragments. | ||

| t | VII+ | Liber Comicus | a#p#c#r# | Lectionary | ||

| v | 81 | VIII/ IX | Veronensis | Heb# | ||

| w | Symbol used in some editions for gue. | |||||

| z | 65 | VIII | Harleianus | (Heb#) | Vulgate Bible (same codex as Z/harl); only Heb. 10:1-end is Old Latin. |

| Symbol | Beuron Number | Date | Name | Contents | Comments |

| d | 5 | V/ VI | Bezae | e#a#c# | Latin side of D (Bezae). Greek does not exist for the Catholics, and of the Latin we have only 3 John 11-15. |

| ff | 66 | IX | Corbeiensis | James | Souter describes it having "some readings unique (almost freakish) in their character...." Overall, it seems to have a mixed text, not affiliated with anything in particular. |

| h | 55 | V | Floriacensis | a#c#r# | Fleury palimpsest. Contains 1 Pet. 4:17-2 Pet 2:7, 1 John 1:8-3:20. The translation is loose and the copy careless, but the text is very close to that used by Cyprian (African). |

| l | 67 | VII | Legionensis | a#c# | Palimpsest; small sections exist of all books of the Catholics except Jude. Said to be close to the Liber Comicus (t) |

| (m) | - | IV? | (Speculum) | eapcr | See Speculum under Fathers |

| q | Symbol used for r in UBS4. | ||||

| r | 64 | VI/ VII | Monacensis | c# | Same as r of Paul. Denoted q in UBS4. |

| s | 53 | VI | Bobiensis | c# | Palimpsest. Old Latin in 1 Pet. 1:1-18, 2:4-10 |

| t | VII+ | Liber Comicus | a#p#c#r# | Lectionary | |

| w | 32 | VI | Guelferbitanus | c# | Palimpsest lectionary, Vulgate with sections in Old Latin. |

| z | 65 | VIII | Harleianus | (c#) | Vulgate Bible (same codex as Z/harl); only 1 Pet. 2:9-4:15, 1 John 1:1-3:15 are Old Latin. |

| Symbol | Beuron Number | Date | Name | Contents | Comments |

| a | 61 | IX | Dublinensis (Book of Armagh) | (ea)p#(c)r | Vulgate text with many Old Latin readings; Paul and the Apocalypse are Old Latin with some Vulgate influence. See D of the Vulgate. |

| g | Symbol used in some editions for gig. | ||||

| gig | 51 | XIII | Gigas | (e)a(pc)r | An immense codex containing the Bible and a number of other works. Its text in the Apocalypse is Old Latin but seems to be a late form of the European type, approaching the Vulgate. |

| h | 55 | V | Floriacensis | a#c#r# | Fleury palimpsest. The translation is loose and the copy careless, but the text is very close to that used by Cyprian (African). |

| sin | 74 | X | a#r# | Contains Rev. 20:11-21:7. | |

| t | VII+ | Liber Comicus | a#p#c#r# | Lectionary |

When discussing the Old Latin, of course, the great question regards the so-called "Western" text. The standard witnesses to this type are the great bilingual uncials (D/05 D/06 F/010 G/012; E/07 is bilingual but is not particularly "Western" and 629 has some "Western" readings but its Latin side is Vulgate). That there is kinship between the Latins and the "Western" witnesses is undeniable -- but it is also noteworthy that many of the most extravagant readings of Codex Bezae (e.g. its use of Matthew's genealogy of Jesus in Luke 3:23f.; its insertion of Mark 1:45f. after Luke 5:14) have no Latin support except d. Even the "Western Non-interpolations" at the end of Luke rarely command more than a bare majority of the Old Latins (usually a b e r1; occasionally ff2; rarely aur c f q).

It is the author's opinion that the Old Latins, not Codex Bezae, should be treated as the basis of the "Western" text, as they are more numerous and show fewer signs of editorial action. But this discussion properly belongs in the article on text-types.

Three Latin versions. Left: The final page of k (Codex Bobiensis), showing the "shorter ending" of Mark. Middle: Portion of one column of Codex Amiatinus (A or am). Shown are Luke 5:1-3. Right: The famous and fabulously decorated Book of Kells (Wordsworth's Q). The lower portion of the page is shown, with the beginning of Luke's genealogy of Jesus (Luke 3:23-26).

As the tables above show, the number of Old Latin translations was very large. And the quality was very low. What is more, they were a diverse lot; it must have been hard to preach when one didn't even know what the week's scripture said!

It was in 382 that Pope Damasus (366-384) called upon Jerome (Sophronius Eusebius Hieronymus) to remedy the situation. Jerome was the greatest scholar of his generation, and the Pope asked him to make an official Latin version -- both to remedy the poor quality of the existing translations and to give one standard reference for future copies. Damasus also called upon Jerome to use the best possible Greek texts -- even while giving him the contradictory command to stay as close to the existing versions as possible.

Jerome agreed to take on the project, somewhat reluctantly, but he never truly finished his work. By about 384, he had prepared a revision of the Gospels, which simultaneously improved their Latin and reduced the number of "Western" readings. But if he ever worked on the rest of the New Testament, his revisions were very hasty. The Vulgate of the Acts and Epistles is not far from the Old Latin. Jerome had become fascinated with Hebrew, and spent the rest of his translational life working on the Latin Old Testament.

Even so, the Vulgate eventually became the official Bible of the Catholic Church -- and, despite numerous errors in the process of transmission, it remained recognizably Jerome's work. Although many greeted the new version with horror, its clear superiority eventually swept the Old Latins from the field.

Vulgate criticism is a field in itself, and -- considering that it was for long the official version of the Catholic church -- a very large one. Sadly, the official promulgation of the Sixtine Vulgate in 1590 (soon replaced by the Clementine Vulgate of 1592) meant that attempts to reconstruct the original form of the version were hampered; there is still a great deal which must be done to use the version to full advantage.

Scholars cannot even agree on the text-type of the original Vulgate.

In the gospels, some have called it Alexandrian and some Byzantine. In

fact it has readings of both types, as well as a number of "Western"

readings which are probably holdovers from the Old Latin. The strongest

single strand, however, seems to be Byzantine; in 870 test passages, I

found it to agree with the Byzantine manuscripts 60-70% of the time and

with

and B only about 45% of the time.

The situation is somewhat clearer in the Epistles; the Byzantine element is reduced and the "Western" is increased. Still, it should be noted that the Vulgate Epistles are much more Alexandrian than the Old Latin versions of the same books.

In the Apocalypse the Vulgate preserves a very good text, closer to A and C than to any of the other groups.

These comments apply, of course, to the old forms of the Vulgate, as found, e.g., in the Wordsworth-White edition. The later forms, such as the Clementine Vulgate, were somewhat more Byzantine, and have more readings which do not occur in any Greek manuscripts.

With that firmly in mind, let us turn to the various types of Vulgate text which evolved over the centuries. As with the Greek manuscripts, the various parts of Christendom developed their own "local" text.

The best "local" text is considered to be the Italian type, as represented e.g. by am and ful. This text also endured for a long time in England (indeed, Wordsworth and White call this group "Northumbrian"). It has formed the basis for most recent Vulgate revisions.

Believed to be as old as the Italian, but less reputable, is the Spanish text-type, represented by cav and tol. Jerome himself is said to have supervised the work of the first Spanish scribes to copy the Vulgate (398), but by the time of our earliest manuscripts the type had developed many peculiarities (some of them perhaps under the influence of the Priscillians, who for instance produced the "three heavenly witnesses" text of 1 John 5:7-8).

The Irish text is marked by beautiful manuscripts (the Book of Kells and the Lichfield Gospels, both beautiful illuminated manuscripts, are of this type, and even unilliminated manuscripts such as the Rushworth Gospels and the Book of Armagh are beautiful examples of calligraphy). Sadly, these manuscripts are often marred by conflations and inversions of word order. Some of the manuscripts are thought to have been corrected from the Greek -- though the number of Greek scholars in the Celtic church must have been few indeed. Lemuel J. Hopkins-James, editor of The Celtic Gospels (essentially a critical edition of codex Lichfeldensis) offers another theory: that this sort of text (which he calls "Celtic" rather than Irish) is descended not from a pure Vulgate manuscript but from an Old Latin source corrected against a Vulgate. (It should be noted, however, that Hopkins-James tries to use statistical comparisons to support this result, and the best word I can think of for his method is "ludicrous.")

The "French" text has been described as a mixture of Spanish and Irish readings. The text of Gaul (France) has been called "unquestionably" the worst of the local texts.

The wide variety of Vulgate readings in Charlemagne's time caused that monarch to order Alcuin to attempt to create a uniform version (the exact date is unknown, but he was working on it in 800). Unfortunately, Alcuin had no critical sense, and the result was not a particularly good text. Still, his revision was issued in the form of many beautiful codices.

Another scholar who tried to improve the Vulgate was Theodulf, who also undertook his task near the beginning of the ninth century. Some have accused Theodulf of contaminating the French Vulgate with Spanish readings, but it appears that Theodulf really was a better scholar than Alcuin, and produced a better edition than Alcuin's which also included information about the sources of variant readings. Unfortunately, such a revision is hard to copy, and it seems to have degraded and disappeared quickly (though manuscripts such as theo, which are effectively contemporary with the edition, preserve it fairly well).

Other revisions were undertaken in the following centuries, but they really accomplished little; even if someone took notice of the revisors' efforts, the results were not particularly good. When it finally came time to produce an official Vulgate (which the Council of Trent declared an urgent need), the number of texts in circulation was high, but few were of any quality. The result was that the "official" Vulgate editions (the Sixtine of 1590, and its replacement the Clementine of 1592) were very bad. Although good manuscripts such as Amiatinus were consulted, they made little impression on the editors. The Clementine edition shows an amazing ability to combine all the faults of the earlier texts. Unfortunately, it was to be nearly three centuries before John Wordsworth undertook a truly critical edition of the Vulgate, and another century after that before the Catholic Church finally accepted the need for revised texts.

Despite all that has been said, the Vulgate remains an important version for criticism, and both its "true" text and the variants can help us understand the history of the text. We need merely keep in mind the personalities of our witnesses. The table below is intended to help with that task as much as possible.

Note that there is no official list -- let alone set of symbols -- for Vulgate manuscripts. Single letters are used by Merk and by Wordsworth/White; the symbols such as am and ful are typical of editions of the Greek text such as Tischendorf. All manuscripts cited in these editions are listed. The quoted comments are primarily from Scrivener; the textual descriptions from Metzger and others.

| Short Symbol | Symbol | Name | Date | Contents | Comment |

| A | am | Amiatinus | c. 700 | OT+NT | Considered to be the best Vulgate manuscript in existence. Copied in England, but with an Italian text. Written in cola et commata, with two columns per page, in a beautiful calligraphic hand. 1209 leaves total. Believed to be the oldest surviving complete Bible in Latin (or, perhaps, any language). |

| -- | and | St. Andrew | ? | e | Formerly at Avignon, but lost by Scrivener's time. |

| ar | see under D | ||||

| B | bigot | Bigotianus | VIII/ IX | e# | "Probably written in France, but both the text and the calligraphy show traces of Irish influence." |

| B | bam | Bambergensis | IX | (e)apc | "One of the finest examples of the Alcuinian recension, and a typical specimen of the second period of Caroline writing and ornamentation." |

| Be or | Beneventanus | VIII/ IX | e | "[W]ritten in a fine revived uncial hand" in cola et commata. Berger describes the text as having the sort of mix of Spanish and Irish readings which underlie the French text. | |

| bodl | see under O | ||||

| C | cav | Cavensis | IX | TO+NT | Along with tol, the leading representative of the Spanish text. Among the earliest witnesses for the three witnesses in 1 John 5:7-8, which it possesses in modified form. The scribe, named Danila, wrote it with a Visigothic hand. |

| c | colb | Colbertinus | XII | (e)apcr | Same as the Old Latin c of the Gospels. Often cited as Old Latin elsewhere, but the text is vulgate. The two sections are separately bound and in different hands. The Vulgate portion of the text is considered to be French. |

| cantab | see under X | ||||

| D | ar or dubl | Dublinensis (Book of Armagh) | VIII/ IX | ea(p)c(r) | Paul and Revelation are Old Latin (#61, cited as a or ar).

Famous Irish codex -- the only (nearly) complete New Testament regarded as being

from an Irish source. Also unusual in that we know a good deal about the scribe:

It was written by one Ferdomnach. The dating is somewhat uncertain. We know from

the Annals of Ulster that Ferdomnach died in 845/6, after a long career.

The book is not itself dated, but there are hints (somewhat confusing) in the

colophon. Ferdomnach is said to have worked under the direction of abbott Torbach

of Armagh, who held that post from 807-808 -- but we also see a reference to

Ferdomnach as "the heir of Patrick," i.e. Abbot or Bishop of Armagh),

which post he held from 812-813. Thus various scholars have dated the work to

807 or to 812. If we must choose between the two dates, I would incline to 807,

since the higher title might have been inserted later. But it is at least possible that the

book took four or so years to complete; it is a major production, consisting not

just of the New Testament but an introductory section, in Latin and Gaelic,

of documents regarding Saint Patrick, followed by the New Testament, and then

a life of Saint Martin of Tours. Brian Boru, the most famous early King of Ireland,

would later add his name to it.

The hand is a small cursive and has been described as "beautiful," though to me it looks rather crabbed. Like most Irish manuscripts, it is handsomely illustrated with figures of animals and the like incorporated into the initial letters, though the only separate drawings are of the four creatures which represent the evangelists. As it currently stands, it consists of 442 pages, mostly in two columns. The Vulgate portions reportedly have an Irish text. The Gospels are said to show signs of correction from Family 13. It includes the Epistle to the Laodiceans. Lacks Matthew chapters 14-19. |

| -- | dem or demid | Demidovianus | XII | OT+NT | Lost; our knowledge is based on Matthei's collation (which included only the Acts, Epistles, and Revelation). Appears to have been Vulgate with many Old Latin readings in the Acts and Epistles. |

| -- | durmach | Durmachensis | VI/VII | e | Book of Durrow. Illuminated manuscript. Colophon (probably copied from its exemplar) states that it was executed by Saint Columba himself. Reportedly close to Amiatinus. The images in this book are a curious mix; the image of Matthew is said to have Anglo-Saxon and Syriac elements, the Markan lion is Germannic and Pictish; the calf symbolizing Luke is again Pictish. The images are not very clear, though they are surrounded by the beautiful swirls and figures of Celtic art. |

| D | dunelm | Dunelmensis | VII/ VIII | e# | Said, probably falsely, to have been written by Bede; it may have come from the Jarrow monastery. Related to Amiatinus. |

| E | mm | Egertonensis | VIII/ IX | e# | Despite having been discovered in France, the text is considered Irish. Many mutilations, especially in Mark. |

| -- | em | St. Emmeram's | 870 | e | "[W]ritten in golden uncials on fine white vellum, a good deal of purple being employed in the earlier pages; there are splendid illuminations before each gospel." |

| Ep or | ept | Epternacensis | VIII/IX | e | From Echternach (Luxembourg), but now in Paris. A colophon associates it with Saint Willibrord (or, perhaps, with a manuscript he owned). Irish hand, and the basic run of the text is said by some to be Irish, but with corrections reported to be of another type (perhaps of the Amiatinus type). Further investigation is probably warranted. The colophon claims a date of 558 C.E., but all agree that it must be at least two centuries later. |

| -- | erl | Erlangen | e | ||

| F | fu, ful or fuld | Fuldensis | 546 | eapcr | Considered, after Amiatinus, the best Vulgate manuscript. Copied for and corrected by Victor of Capua. Italian text. The Gospels are in the form of a harmony (probably based on an Old Latin original, and with scattered Old Latin readings). Includes the Epistle to the Laodiceans. |

| for | see under J | ||||

| -- | foss | St. Maur des Fossés | IX | e | |

| G | Sangermanensis | IX | OT#+NT | Old Latin in Matthew (where it is designated g1). French text with some Old Latin elements. Order of sections is eacrp. | |

| -- | gat | VII-IX | e | Referred to Saint Gatian of Tours. Said to resemble Egertonensis (E) in text, and to have many Old Latin readings. There are many variant readings in the text, usually vulgate and old Latin, written between the lines. | |

| -- | gig | Gigas Holmiensis | XIII | e(a)pc(r) | Same as gig of the Old Latin. Rarely cited as a Vulgate witness, as the Vulgate text is late. |

| gue lect | see gue among the Old Latin witnesses in Paul | ||||

| H | hub | Hubertianus | IX/ X | OT+NT# | Original text may have been Italian (close to Amiatinus); it has been corrected (often by erasure) toward Theodulf's revision. Three columns per page. The text breaks off at 1 Pet. 4:3. The hand is said to "strongly resembl[e]" that of Q. |

| harl | see under Z | ||||

| I | ing | Ingolstadiensis | VII | e# | Many mutilations, especially in Matthew (only 22:39-24:19, 25:14-end remain of that book). |

| J | for | Foro-Juliensis | VI/ VII | e# | Italian text. A legend, obviously false, has it that the portion of this manuscript at Prague was part of the original the Gospel of Mark! Distributed across several libraries. The Markan portion is often illegible, and the final chapters of John are fragmentary. Portions of Mark (at Prague) cited by Tischendorf as prag. |

| J | juv | Juvenianus | VIII/ IX | acr | |

| K | kar | Karolinus | IX | OT+NT | Alcuin's revision. Called "Charlemagne's Bible." |

| L | Lichfeldensis | VII/ VIII | MtMk Lk# | Formerly designated Landavensis. Illuminated manuscript with an Irish text. (The writing is describes as "Irish half-uncial.") Contains Matt. 1:1-Luke 3:9. Legend attributes it to St. Chad. | |

| L | VIII | p | Written in a Lombard hand. | ||

| L | Lemovicensis | IX | c | "Mixed" text, containing a part of 1 John 5:7. | |

| -- | lux | Luxeuil | IX | (e) | |

| M | med | Mediolanensis | VI | e# | Italian text, considered by Wordsworth & White to rank with Amiatinus and Fuldensis. Assorted lacunae (Matt. 1:1-6, 1:25-3:12, 23:25-25:41; Mark 6:10-8:12) and a few small supplements (Mark 14:35-48; John 19:12-23). Has "interesting lectionary notes in the margins." |

| M | Monacensis | IX | acr | "Good text, but rather mixed, especially in the Acts, where there are strange conjunctions of good and bad readings." Written in "large rough Caroline minuscules." | |

| M | Monacensis | VIII | p | ||

| mac-regol | see under R | ||||

| mart | see under MT ( | ||||

| mm | see under E | ||||

Ma | mt or mart | Martini-Turonensis | VIII/ IX | e | "[G]old letters, interesting text." |

| N | V | e# | Palimpsest. Text is regarded as very valuable. | ||

| O | bodl or ox/oxon | Bodleianus or Oxoniensis | VII | e# | Legend has it that this was given by Gregory the Great to Augustine of Canterbury. "British" (i.e. Italian?) text. |

| O | Seldenianus | VII/ VIII | a# | Described as "most valuable." Lacks 14:26-15:32. | |

| O | Bodleianus | IX | p# | "Irish hand." Colossians follows Thessalonians. Hebrews breaks off at 11:34. Has been heavily corrected by three different hands. The text of the first hand may have been Old Latin (designated x). | |

| P | pe or per | Perusinus | VI | Luke# | Luke 1:1-12:7, mutilated. Purple manuscript. |

| prag | see under J | ||||

| Q | Kenanensis | VII/ VIII | e | Book of Kells (now in Dublin). Generally considered to be most beautiful illuminated manuscript in existence; there is at least some colour on all but two of its 680 pages. Irish text, said by Metzger to have "a peculiar fondness for conflate readings." (An extreme example comes in Matt. 21:31, where, when asked which of the sons did the will of the father, some vulgate texts say "the first," others, "the last"; Kells reads "the first and the last"!) | |

| R | mac-regol | Rushworthianus | VIII/ IX | e | Rushworth Gospels (so called for the seventeenth century owner who donated it to the Bodleian Library), written by a scribe named Mac Regol who reportedly died in 820 C.E. (Hopkins-James, however, says Mac Regol or "MACREGUIL" died in 800 and was Bishop of Birr; Hopkins-James doubts he was the actual scribe.) Has an interlinear Anglo-Saxon gloss (Matthew in Mercian, Mark-John in Northumbrian; they are listed as the work of scribes named Farman of Harewood and Owun). Skeat declared it to be close to the Lindisfarne Gospels, but Hopkins-James disagrees strongly and says it has a Celtic (Irish) text. Reported to show many alterations in word order. |

| R | Reginae Sueciae | VII/ VIII | p | Italian text -- one of the best in Paul. | |

| -- | reg | VIII? | e# | 54 leaves of Matthew and Mark, containing less than half of each. Gold uncials, purple parchment. Many old readings. | |

| S or S | san | Sangallensis | V | e# | Oldest surviving manuscript of the Vulgate Gospels; only about half the leaves have been recovered from manuscript bindings. Italian text, of "remarkable" value. |

| S | ston | Stoneyhurstensis | VII | John | Reportedly found in the coffin of Saint Cuthbert. "A minute but exquisitely written uncial MS. with a text closely resembling A[miatinus]." |

| S | Sangallensis | VIII | ar | "Text interesting but mixed." Written by a monk named Winithar. Contains extra-biblical matters as well as the Bible text. | |

| -- | san | VI | e# | Matt. 6:21-John 17-18, sometimes fragmentary. The scribe claims to have compiled it from two Latin manuscripts with occasional reference to the Greek. | |

| -- | san | VI | p# | Palimpsest (lower text Latin martyrology). Contains Eph. 6:2-1 Tim. 2:5 | |

| -- | theo or theotisc | Theotisca | VIII | e# | Matthew 8:33-end, mutilated. Old German text on facing pages. |

| T | tol | Toletanus | VIII | OT+NT | Along with cav, the leading representative of the Spanish text. Among the earliest witnesses for "1 John 5:7-8," which it possesses in modified form. Written in a Visigothic hand, it was not new when it was given to the see of Seville in 988. |

| Th or Q | theod | Theodulfianus | IX | OT+NT | Theodulf's revision, possibly prepared under the supervision of Theodulf himself. The Gospels and Psalms are on purple parchment. |

| -- | taur | Taurinensis | VII? | e | |

| U | Ultrarajectina | VI | Mt#Jo# | Matt. 1:1-3:4 and John 1:1-21, bound with a Psalter and written in an "Anglian hand" resembling Amiatinus. | |

| U | Ulmensis | IX | apcr | "Caroline minuscule" hand. Includes Laodiceans. Now in the British Museum. | |

| V | val | Vallicellanus | IX | OT+NT | Alcuin's revision, written in Caroline minuscules. Considered the best example of this type. |

| W | Willelmi | 1254 | OT+NT | Written by William of Hales for Thomas de la Wile. Cited by Wordsworth as typical of the late mediaeval text. | |

| Wi | Wirceburgensis | VIII/ IX | p | ||

| X | cantab | Cantabrigiensis | VII | e | Said to have been corrected toward a text such as Amiatinus. Like O, legend has it that Gregory the Great sent it to Augustine of Canterbury. |

| Y | lind | Lindisfarnensis | VIII | e | Illuminated manuscript with interlinear Anglo-Saxon gloss (old Northumbrian dialect). Second only to the Book of Kells in the quality of its illuminations (some would esteem it higher, since it uses less garish colors). Italian text, very close to Amiatinus. Written by scribes directed by Eadfrith, bishop of Lindisfarne (fl. 698-721 C.E.) in honour of St. Cuthbert. |

| Z | harl | Harleianus | VI/ VII | e | Italian text, "in [a] small but very beautiful hand, and with an extremely valuable text." |

| Z | harl | Harleianus | VIII | pcr# | "Written in a French hand, but showing traces of Irish influence in its initials and ornamentation; the text is much mixed with Old Latin readings; it has been corrected throughout, and the first hand so carefully erased in places as to be quite illegible." The base text is late Vulgate, but there are many early readings. The Old Latin portions are designated z. Rev. 14:16-end have been lost. |